It’s time to talk tinnitus. I’m borrowing the title from a podcast that I found really helpful. Run by a group of volunteers with tinnitus, I went through all the episodes and learned a lot. The guests are great, the interviewers are well-prepped, they get right down into the nitty gritty and really get across the lived experience of lots of people with tinnitus, and it sounds great, which is a big deal for the target audience. There are even transcripts for people who are struggling to hear the episode.

I did not venture into the related tinnitus forums. There are only so many hours in the day and there’s a level of digital overload that you could get into, a rabbit hole where you’re constantly feeding on the varied trauma wrought on the lives of others. I keep my reading focused. Forums for sudden hearing loss and cochlear implants for single-sided deafness. There are so many different types of hearing loss and resultant tinnitus that it’s important to realise that some people have different problems to you and you need to focus on your own situation. I feel this is quite relevant too in the context of general tinnitus advice that may not be helpful for all forms of tinnitus or could be frustrating to those with more severe forms of tinnitus.

For an intro to tinnitus, you can start here. I’ll start with my experience of tinnitus and move on to some of the academic work in this area and try to show how the two align.

Tinnitus was not a foreign concept to me. My Dad had mild tinnitus after noise-related hearing loss. Some Irish towns had a significant sugar beet dependency and Tuam was one of them. Working as a fitter/welder in the Sugar Factory in the 1970s was a pretty good recipe for hearing loss. He feels the tinnitus is gone now. Our combined hearing loss has an impact on our walks together. Both of our good ears are on the right, so it’s a struggle to have a clear conversation (unless I walk backwards). I’ve known his good side for years and I always walk on that side, but I’m considering lining up our audiograms as his bad side is a lot better than mine and we may need to swap sides for future walks.

I had heard of musicians with tinnitus. Pete Townsend and Ryan Adams were the two that stuck out- a rogue’s gallery. In the teenage garage band years we had played at loud volumes, but we were cognisant of the need to limit exposure and take breaks. An older sound engineer told us about the permanent severe tinnitus that he had and that his warnings to younger musicians always seemed to fall on deaf ears (sorry). We got the message. We had also heard of some sound systems where a noise limiter would cut power to the stage if you breached a decibel threshold multiple times. The University College Dublin bar had a system like this. Some guitarists had priority issues, worrying about the health of their tube amps when the power dropped rather than their hair cells being shredded. Thankfully, younger tech-savvy musicians are more likely to play with in-ear monitors at a controlled volume now rather than rely on floor monitors that blast them with sound so that they can hear their part in the overall sound mix.

In the initial days of my hearing loss I don’t think that the tinnitus was very noticeable. I remember listening to music and it was like the left side of the stereo track was silent with no noise replacing it. There was some tinnitus at the early audiograms with a comment from an audiologist that it might be a good sign of my brain adapting or my hearing recovering.

There was some assessment of my tinnitus in the booking questionnaire with the audiologist who did my back to work audiogram. I don’t think my score was in the severe range at that stage- I had a pretty quiet, solitary existence: hyperbaric chamber, long walks and avoiding people/COVID so that my treatment wasn’t interrupted. I was off work still and there was minimal noise at home.

Getting back to work changed how I experienced tinnitus. I was frequently in (relatively) loud environments and there were lots of online meetings with a headset. The tiredness/listening fatigue probably affected the tinnitus too. I explained my tinnitus at home and to colleagues using this video. My tinnitus was a mix of 2, 4 and 9. The volume varied depending on the environment and sound level. A loud, reverberant space like the cavernous canteen at work was impossible to stay in. I suppose I was experiencing a mix of hyperacusis and tinnitus. I found that exposure to noise raised the level of my tinnitus. This could range from the sound of the water in the shower in the morning to the din of a noisy restaurant. Each morning the level of the tinnitus would reset back to the usual (loud) baseline. On noisy restaurant nights (there weren’t too many), I would be awake for a couple of hours after with the tinnitus volume. In the morning the process would start again.

I saw a post on Twitter from someone who was six years post-SSNHL and subsequent dominant tinnitus.

I asked him where I can collect my 3 month medal. I also felt like intermittently playing the tinnitus simulation for the different people around me and reminding them that it’s still there and not really improving. As tinnitus is pretty common, I can talk about it and compare experiences with other people, it was sometimes helpful to see your own experience mirrored in theirs. The interwoven tinnitus and tiredness tended to get worse as the week progressed. My job still got everything that was needed as it did prior to my hearing loss, but it was leaving me with very little capacity for life beyond work. I began to call it Tinnitus Thursday and knew that I needed to initiate the conversation about changing my working week.

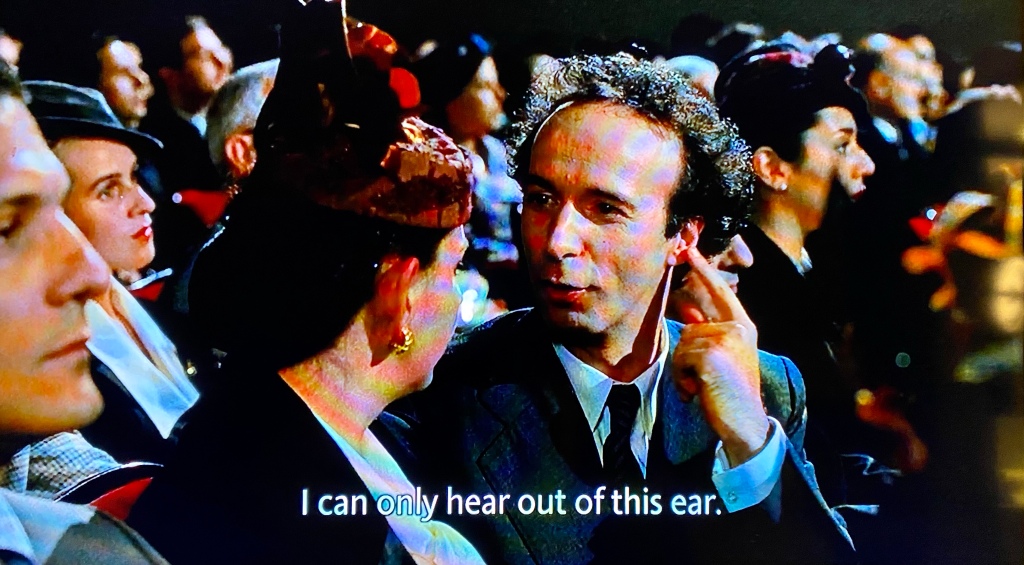

Work wasn’t the only challenge to the tinnitus. The sounds of a reverberant kitchen were pretty unpleasant. Likewise, when the kids were fighting. Violins and tin whistles were hard work. I thought I would never go to a gig again. There were a couple that I managed (tickets for both were bought prior to my hearing loss). Big Thief provided the first post-Covid outing for my eldest who had a long hiatus in her live music curriculum following Franz Ferdinand and The Divine Comedy in 2019/2020. I looked at various forums in preparation to learn from the experience of others. It ranged from ruling out gigs altogether to returning with earplugs and accepting the resultant hyperacusis/tinnitus. My number one priority was protecting my remaining hearing (and my daughter’s). I had to accept that there would be tinnitus and there was a price to pay when getting back out into the world. Silicone earplugs cut the volume considerably and made the gig manageable. The sound was not as I would have chosen, but it was better than being at home with a similar level of tinnitus and missing a band in their moment. I inclined my good ear to the band and spent a lot of time looking in the direction of the woman next to me. I explained. She understood.

A few months later and I’m in Heathrow awaiting a flight home following a long awaited/deferred Pearl Jam & Pixies gig with my band mates of old. Apart from raging tinnitus and my silicone earplug, the strangest part of the gig was the gaggle of babies and wobblers (in ear-protecting headsets, thankfully). Their parents had evidently bought these tickets before they were on the scene. At the departure gate I stumbled upon a blog by Sarah Chapman called “From Ear to Eternity”. It was fantastic. Sarah is a Nurse and specialist in communicating health information who works for the Cochrane Collaboration. Although she has a different kind of hearing loss to me, the blog was incredibly useful. I’m glad that a lot of my experience to date has been documented too. There’s work to be done in sharing it for people in a similar boat to me in the future to empower them to seek the best possible hearing they can get. It’s great to read of someone’s experience of the cochlear implant process.

While tinnitus is pretty crap, life does go on and you start to adjust. I’m glad I was not in the catastrophic tinnitus category. I could sleep, mostly. There were probably people out there with louder tinnitus. I had learned that it’s possible to have a good time while you have severe tinnitus. There were nights out at a wedding and a staff dinner that were feasible and enjoyable with a few adjustments. Regular breaks from noise at the wedding and an incredibly thoughtful organiser of the staff night out who got a private section of a pub/restaurant where I could hear people and the tinnitus stayed under control. Also- spoiler alert- I knew that I would get a CI one way or the other and that the duration of my tinnitus was hopefully finite. I had also settled in my head that it would be easier to adjust to the tinnitus and habituate if I had exhausted all treatment options, just like going after the hyperbaric treatment at the outset.

One challenging aspect of tinnitus is people’s responses to it, including those of health professionals. Some of the themes included:

– the severity is down to how you respond to it/focus on it

-the ever-present “ignore it and it will go away- learn to live with it” approach

-the assumption that tinnitus is one generic thing: “just stick on the radio and it will be gone”, reduce your stress levels, and salt intake

-if you don’t follow the programme or diet or take the very expensive supplement, it’s your own fault if you don’t habituate as you didn’t do it right (reminded me of this sketch)

Part of the issue is the prevalence of mild/intermittent tinnitus in the general population. With mild tinnitus being very common, there can be poor understanding of severe or catastrophic tinnitus that causes significant levels of distress and can greatly diminish quality of life.

No one is setting out to harm or cause upset, but it is frustrating all the same. Some of the more harmful attitudes may be influenced by early papers on tinnitus, e.g. the 1999 paper defining tinnitus types asserts that: “Much of the severity of tinnitus relates to the individuals’ psychological response to the abnormal tinnitus signal”. This paper separated tinnitus into slight, mild, moderate, severe and catastrophic based on the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory score. A more recent paper suggests three distinct tinnitus types based on associated hearing loss and tinnitus severity. It’s great to see how the literature has moved on in the time period from quite judgemental and with definite errors e.g. “The presence or absence of hyperacusis may have relevance to the overall condition of the individual concerned but is irrelevant to the severity of any tinnitus.”, towards an enquiring, progressive approach that may help direct patients towards more effective, tailored care. After looking at both papers, I spot name common to both- Prof. David Baguley. I recall an outpouring of grief at his premature death in 2022. In reading Prof. Baguley’s obituary it’s evident that the audiology/ENT world have lost someone who deeply cared about progressing care for people with hearing loss and tinnitus. RIP.

As I look at the tinnitus literature, I get a sense of the complexity and how little I know. I’ll probably make a start with the updated version of the book Prof. Baguley wrote with colleagues.

I remember telling the audiologist in the hospital during my initial workup that I had minimal tinnitus and that I was trying not to put a name on it and pay it no attention. I visualised it locked inside a small aluminium box with rounded corners. But over time it broke out. I now think that the brain changes involved happened over a period of weeks to months. I began to see parallels with phantom limb pain and thought of my auditory cortex and how it was suddenly deprived of input from my left ear. As part of this process, my auditory cortex turned up the volume to try to eke out some sense from the incoming radio silence. When that didn’t work, it started making up expected sounds. This ranged from a general increase in the volume of the white noise mess with sound exposure to very specific sounds being echoed on my left side with a short delay e.g. the sound of nail clippers. The normal acoustic click in my right ear, followed by a patch of louder white noise of the same duration on the left. This also happened with the clink of cutlery or the smash of a dropped baking tray. This reactivity – specifically to a sharp sound and generally to the overall environmental din was very real to me, but reactive tinnitus was not something that a lot of people were familiar with and its existence was denied by some health professionals. On the cochlear implant for single sided deafness forum- there was emphatic agreement when people described this as “cross-over” or “reactive” tinnitus. Maybe an audiologist can point me in the direction of academic literature on this phenomenon. The one thing that I took from the forum replies: this was stopped by a cochlear implant.

A cochlear implant seemed to be my best chance of getting back to some degree of normality, so I didn’t spend time pursuing other ways to manage my tinnitus. If the CI route was not open to me, I would have found an audiologist to guide me through the process of picking the right approach to manage my tinnitus. I think I would also have sought out cognitive behavioural therapy options generally or specifically for tinnitus.

An essential part of the tinnitus story for me was getting it assessed (semi-)objectively. When I was being assessed for a cochlear implant at a German hospital, the audiologist did a very simple assessment that I hadn’t encountered previously. She used simulated tinnitus in my good ear to find something that approximated my tinnitus. She then told me to listen carefully and tell her when the volume in my good ear matched or exceeded my bad ear. I noticed her eyes widening as she went up and up. We had been doing a regular audiogram beforehand and maybe it pushed up my tinnitus levels. I stopped her when she got to 83 decibels. If you want some context for relative noise levels, there are more details here. 83 decibels is in the territory of a whistling kettle, a blender or a noisy restaurant. My sounds are white noise/waterfall/the sound of water turning to steam on hot rocks. The best way that I can describe the volume is to think about carrying around a hairdryer with you at arm’s length every waking hour. Sometimes it’s on a lower setting, but if you really want to get out there and live and interact with people (and not go around telling people to be quiet), it’s going to be on the loudest setting. The audiologist said “Oh my goodness” with a heavy German accent. It meant a lot for someone else to get what I had been carrying with me for a long time. I wasn’t crazy and this was real. I wasn’t sure at this point if I would be eligible or not, but I was certain that I would walk to Berlin if needed to stop the tinnitus.

I don’t believe in miracle cures. Unfortunately, people in desparate situations want to believe that there is a quick way out. There are plenty of people out there who will push “cures” out of goodness, ignorance or the sheer love of making money. There are regular posts on the forums with people disappointed after paying $700 a month for supplements that promised to fix tinnitus. Peddlars of non-evidence-based treatments need to be weeded out of the tinnitus ecosystem. They are inadvertently (or very explicitly) taking advantage of people in a shitty situation and there are significant opportunity costs involved when you go down therapeutic dead ends.

So what are the evidence-based treatments for my situation? There is a very relevant 2019 study from my friends in Charité, Berlin, where I eventually get my cochlear implant. This study aimed to investigate the influence of treatment with a cochlear implant (CI) on health-related quality of life, tinnitus distress, psychological comorbidities, and audiological parameters. The study looked back at the records of 20 people in my situation (65% female, 21-80yrs, average duration of deafness before implantation was 4.8 years (range 0.3–26.9 years), assessments were completed about 1.5 years post-implantation. They used a standardized testing framework, essentially a common set of goalposts intended to be used in multiple studies so that they’re comparable. This testing is very comprehensive and intended for research rather than routine assessment of CI candidates or recipients.

Improvements in this study included:

- Better health-related quality of life (including basic and advanced sound perception, self-esteem and activity)

- Better overall quality of life

- Decreased tinnitus-related distress

- Improved tinnitus: “Seventeen of 20 patients (85%) reported tinnitus before implantation. After implantation, for the implant on situation, tinnitus decreased in 12 patients, 3 of them reported complete disappearance of tinnitus. However, 4 patients had an increase in tinnitus distress and 1 patient reported no change. In the 3 patients who were tinnitus-free before surgery, implantation did not induce tinnitus”

- Tinnitus questionnaires demonstrated improvements in emotional distress, intrusiveness and auditory perceptual difficulties

- Anxiety symptoms

- Hearing performance- % word understanding and speech in noise tests

Importantly, neither duration of deafness nor age affected auditory performance.

Another study from the same group followed people from pre-op to six months post-op. This study had 21 patients (62% female, 25-80 years). There were improvements in quality of life and cognitive distress. Elevated stress levels prior to surgery decreased significantly. Psychological problems like depression and anxiety also improved. Hearing ability was recovered, especially with regard to directional hearing.

There is a very important point about both studies- they’re tiny. This is not a criticism of the researchers. For studies this small to demonstrate a wide range of statistically significant differences is impressive. If I saw a study of a drug with this level of effectiveness in real world studies, I would be very impressed, and, health services/insurers would definitely fund it. I can’t believe that people in various countries have been left with their brains slowly getting cooked by extreme tinnitus when such an effective intervention is available.

Some randomised controlled trials (RCT) have looked at the impact of CIs on tinnitus and a range of other hearing outcomes. A French study that included an RCT of immediate CI versus delayed CI (6 months) found that the immediate CI group had significant improvements in self-reported tinnitus severity at six months compared to those randomised to delayed CI. Another RCT showed that CIs outperformed Contralateral Routing of Sound (CROS) and Bone Anchored Hearing Aids (BAHA) for most outcome measures.

A Belgian study, from the legends that published the initial work on cochlear implants for incapacitating tinnitus in 2008, examined the long-term tinnitus outcomes in CI recipients. The study included 23 patients with unilateral deafness and incapacitating tinnitus. Incapacitating tinnitus was defined as a score above 6 on a visual analogue scale (VAS) (a 10cm line anchored by ‘Quiet’ (at 0) and ‘Very loud, can not get any worse (at 10)- the patient marks the point on the line which represents the loudness of their tinnitus). These patients were using their CIs for between 3 and 10 years. The paper shows impressive reductions in the VAS tinnitus scores and improvements in the tinnitus questionnaire into the long term. All 23 patients were still wearing the CI daily and 22 reported that putting on and taking off their CI was the first and last thing they did each day. I’ve never seen medication adherence statistics that match that degree of patient adherence to a treatment.

A more recent systematic review (systematic search for all papers on a topic and analysis to combine their results) demonstrated that among the 50 included studies involving 674 patients, cochlear implantation in adults with SSD resulted in significant improvements in speech perception scores in quiet and noise, tinnitus control, sound localization, and quality of life.

The alternatives that were on offer to me at the time in the Irish health system were CROS hearing aids or possibly a BAHA. From my reading, both would be less effective than a cochlear implant for me. Both CROS and BAHA approaches rely on routing sound to the better ear. Neither result in binaural hearing. Before I even read that CROS aids are often poorly tolerated in SSD, I knew myself that I didn’t want anything impeding hearing in my good ear as I could function at work with appropriate placement and did not want to mess with that. The additional stimulation in my good ear would also have exacerbated my tinnitus.

Based on this work, I knew that I needed to try to get assessed for a cochlear implant. In the meantime, I preferred quiet settings. I spent more time on my own than usual, seeking silence.